NOTE: This text appeared originally in Spanish on the magazine Numinis as El poder de una sencilla palabra.

He is wearing a crimson knitted waistcoat with a V-neck from which the sleeves of a shirt with thick vertical gray and white stripes emerge. The white collar of the shirt is adorned with the knot of a black tie that disappears beneath the waistcoat. The shirt cuffs are white, fastened by two jet cufflinks; the trousers are black. A man of seventy-one, a true gentleman, who still has almost twenty more years of life ahead of him, though he doesn’t know it. He has risen from his seat to look for a book among the hundreds that fill the shelves covering the entire wall. His interlocutor, much younger than he, has asked him a question, and he wants to answer it by reading a passage from a book. In his right hand, he holds a pipe with a black stem and a red sandalwood bowl. His hands. Those hands… His mother, for whom self-pity was nauseating, had forced him to use both hands from a young age as if that atrophied right arm, present since birth, didn’t exist. He searches among the books. One minute, two minutes… “It’s impossible to find it, it’s sixty – two years of reading,” the other person tells him. “No, no. It’s not impossible,” he replies. After almost three minutes, he takes out a book. He skims through it. He looks at the index. He skims. He searches. Finally, a smile lights up his face. He has found it. He returns to his seat. He hears the barking of the little dog in the other room. She is hungry, but she will have to wait. Then, he looks at the young man who sits down opposite him in another armchair and begins to speak:

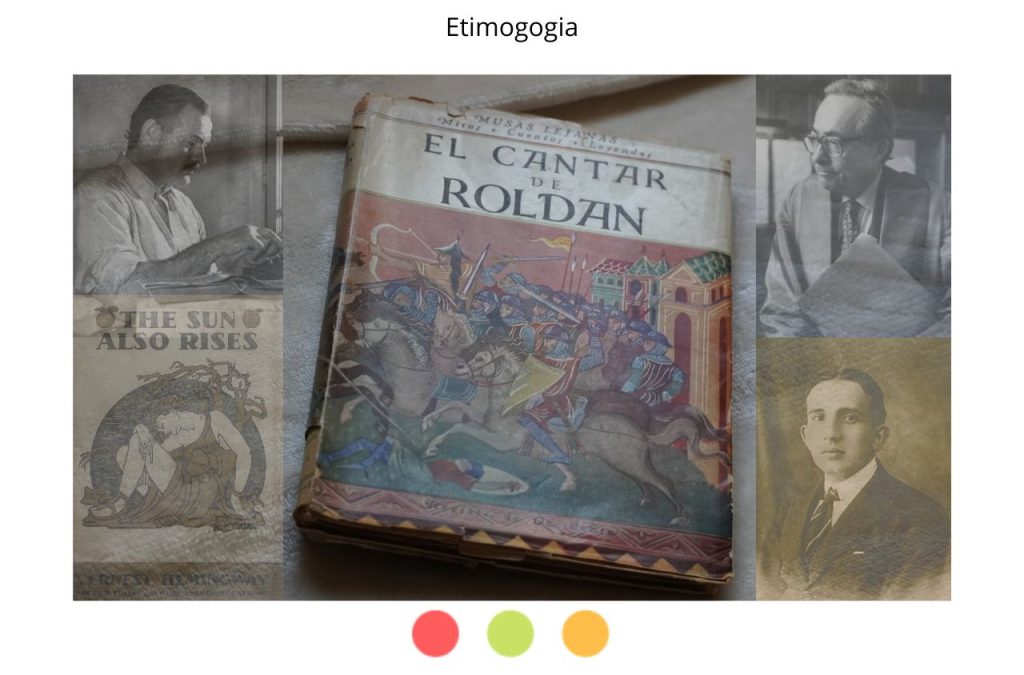

“One of the passages that illustrates my concern about the lack of understanding of great references by most people, about people becoming deaf to the most moving literature, is a small passage from the novel The Sun Also Rises — the title refers, of course, to Ecclesiastes — which in the Spanish version is known as Fiesta. This is the situation: two very good friends are on a bus and believe that they love each other, that they are truly sincere and loyal to one another. I’m going to read this passage to you:”

We went through the forest and the road came out and turned along a rise of land, and out ahead of us was a rolling green plain, with dark mountains beyond it. These were not like the brown, heat-baked mountains we had left behind. These were wooded and there were clouds coming down from them. The green plain stretched off. It was cut by fences and the white of the road showed through the trunks of a double line of trees that crossed the plain toward the north. As we came to the edge of the rise we saw the red roofs and white houses of Burguete ahead strung out on the plain, and away off on the shoulder of the first dark mountain was the gray metal-sheathed roof of the monastery of Roncesvalles.

«There’s Roncevaux,» I said.

«Where?»

«Way off there where the mountain starts.»

«It’s cold up here,» Bill said.

«It’s high,» I said. «It must be twelve hundred metres.»

«It’s awful cold,» Bill said.

He closes the book, looks at the young man he’s talking to, and makes the following reflection:

“In the epic poem The Song of Roland, Roncesvalles is the site of a terrible betrayal. Count Roland, Charlemagne’s nephew, and his friends are betrayed by one of their own, Count Ganelon, who is also Roland’s stepfather. In league with Ganelon, the Saracens, led by the Moorish king Marsil of Saragossa, ambush Roland and his friends at Roncesvalles and brutally butcher them. The very clever author of The Sun Also Rises, when he refers to Roncesvalles with this simple word, is actually suggesting that a great betrayal is about to take place there, that the two friends are on the verge of breaking their bond, that they will ultimately betray each other. That’s why Bill keeps repeating, «It ‘s cold up here ,» «It ‘s awful cold.» He ‘s not referring to the weather… it’s the icy cold of the heart.”

His eyes well up with an emotion that rises from deep within. Only a great artist can say everything without saying anything. What saddens him most is that most people no longer recognize Roncesvalles and that future editions of the novel will probably require a footnote explaining it, which kills the whole story. When The Sun Rises was published in 1926, it was a huge success, and the general public recognized the profound significance of Roncesvalles. We are reaching a point where we will have to add footnotes for everything and won’t even recognize the profound meaning of La Mancha …

In 1926 a splendid Spanish translation of The Song of Roland also appeared. It was made by Benjamín Jarnés and published in Revista de Occidente. The Sun Also Rises was translated as Fiesta into Spanish, in Argentina in 1944. It did not arrive in Spain until 1948. The second edition of El cantar de Roldán by Benjamín Jarnés is from 1945. Would the Spanish public of that time understand the meaning of Roncesvalles?

Our gentleman with the atrophied right arm returns the book to the niche from which he had taken it. A barking comes from the other room. The little dog will have to be fed. Hardly anyone remembers Benjamin Jarnés anymore. Nor are these times for Durendals or Hautecleres. He lights his pipe. He inhales. He becomes thoughtful. He exhales slowly, and a wisp of smoke carrying scents of yesterday vanishes into the thin air. The past returns to him the awareness of the present, which warns him of a future where fewer and fewer people will recognize the power of a simple word.