This article appeared originally on the magazine Numinis in Spanish as Y que giren veloces los husos.

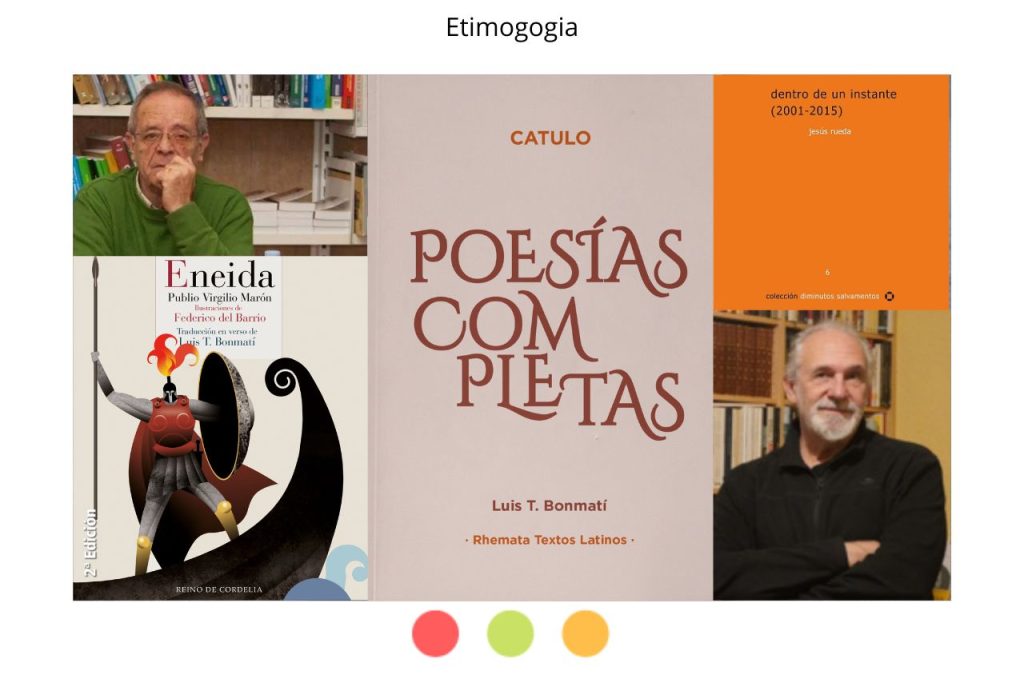

“I’m going to be a bit of a rogue. I would recommend Catullus, the Roman writer… well, he wasn’t from Rome, but from northern Italy. I would recommend his poetry, because it completely breaks the mold of his time, of all times, of his society, of the prescribed order, of absolutely everything. And I think that’s important: to be critical enough to know what ’s going on around you,” that’s what he said. More than two months have passed since that conversation. We were in his place, a small apartment in a busy Madrid neighborhood, sitting across from each other. He had offered me a coffee, which I slowly sipped. Books overflowed the shelves; stacks of them grew from the floor like mushrooms, defying gravity and forming circus-like balances. Just a week earlier, his first violin concerto had been premiered at the Teatro Monumental. Jesús Rueda is a composer and a reserved, introverted man — introverted in the sense that he looks inward to fulfill the maxim of «know thyself «— and a very good conversationalist. When I asked him what book he would recommend reading before dying, this is what he said: Catullus, the poetry of Catullus.

I’m obedient and usually follow the recommendations of people I admire. I won’t say that as soon as I left his place I went straight to a bookshop to get a book by Catullus. I suppose that day I sinned, yes, in thought and inaction: I probably thought about buying the book, but I didn’t. A double sense of guilt for wanting to buy and not buying, for wanting to read and not reading. I neither bought it nor read it, perhaps also guided by a maxim that has accompanied me for some years now: books find you. That’s how Dentro de un instante (Within an Instant), the book of aphorisms written by Jesús Rueda, found me, and I was surprised to discover that Jesús not only composes music, but also writes texts and reads a lot. To paraphrase that proverb attributed to the Spanish author Miguel de Cervantes: he who reads much and travels much, lives much. Jesús Rueda is a bon vivant, because he silently savors life, without disturbing anyone, knowing himself or at least striving to it.

That happened more than two months ago, as I’ve already written. And it wasn’t until four days ago that Catullus‘s Complete Poems found me. I have to explain, because for a book to find you, all sorts of twists and turns of fate must occur beforehand. Chance —another name for destiny, as Emilio Pascual said— brought me to Luis T. Bonmatí about a month and a half ago. First came La llanura fantástica (The Fantastic Plain), then Cuentos del amor hermoso (Tales of Beautiful Love), then Último acorde para la Orquesta Roja (Last Chord for the Red Orchestra), and later, the Aeneid. The Aeneid is by Virgil, but there is a splendid translation in Spanish in hendecasyllables by Luis T. Bonmatí. I haven’t read Virgil, because I don’t speak Latin. The one I have read is Luis T. Bonmatí. I mean, the adventures, misadventures, joys, and sorrows I know of Aeneas I know thanks to Luis T., not Virgil. Furthermore, with Luis T., I’ve broken one of my maxims —and that makes three; too many maxims for a text, too few for a lifetime— namely: I don’t read translations. Let me clarify something. I don’t write that T with a dot to sound interesting or to lift the veil of mystery surrounding Bonmatí. The T. comes from Trinitario. So his name, there you have it!, is Luis Trinitario, a name not at all unusual in Catral, the Levantine town where Bonmatí was born. As far as the annals of gossip go, it seems that his grandfather was named Trinitario, and then came an uncle with the same name, and two cousins as well. Perhaps Bonmatí’s mother thought that after him a girl would come along, and so that his father’s name wouldn’t be lost, she gave Luis the name Trinitario. However, Bonmatí’s mother never had a daughter. So when the next son was born after Luis, she simply named him Trinitario. There are three brothers. Since there are so many Trinitarios in the family, they are usually shortened to Trinos. Anyone who goes to Catral and asks about the Trinos will probably end up reading La llanura fantástica.

I’ll get back to the point, I always get sidetracked. I was saying that four days ago I came across the Complete Poems of Catullus, but not because I was looking for Catullus, but for Luis T. «What a coincidence!,» I said to myself, «I’m going to kill two birds with one stone: fulfill Jesús Rueda’s recommendation and read Bonmatí!» And that ‘s what I did.

It’s a well-known fact that when a book is revealed to you, many other mysteries are unveiled. Bonmatí’s translation edition is bilingual, meaning that the original Latin text is accompanied by the Spanish version. It turns out that the complete poems of Gaius Valerius Catullus in Latin are called Catulli carmina… Forgive me, experts! I hadn’t associated that title with a work by the composer Carl Orff that bears the same name, because everyone knows Carl Orff for the «O Fortuna» from Carmina Burana that populates films, television series and commercials.

Through Luis T.’s prodigious lens, I’ve come to know Virgil’s Aeneas, the Aeneas who appears in Henry Purcell’s well-known opera —at least the heartbreaking aria When I am laid sung by Dido before her death is well-known. Dido and Aeneas … It goes without saying that reading the love story of Dido and Aeneas in the Aeneid is not the same as hearing it, albeit skewed, in Purcell’s opera. And through that same prodigious, poetic lens of Luis T., I’ve come to know the scoundrel, the shameless, cruel, yet profoundly human Catullus, who doesn’t pull any punches.

How unpredictable life is! Perhaps those three Fates, spinners of human existence, were right when they sang in unison at the wedding of Thetis and Peleus: «And let the spindles turn swiftly as they weave the warp of Destiny!»